How to record tree form

Trees can come in a wide variety of shapes, and this often depends on their age and how they’ve been used or managed. Here are the tree forms which you can record with the Ancient Tree Inventory.

What can we learn from the form of a tree?

- Describes how the tree has grown

- Indicates past or present management

- Helps identify historic treescapes e.g. pollard and coppice, wood pasture

- Dictates where girth is measured (for consistency in recording)

- Clarifies girth measurements (validates unexpected sizes e.g. multi stem trees)

- Can confirm historical evidence of former site management (e.g. boundaries and woodbanks)

- Helps others analyse the data and provides useful evidence

The tree form option that you select is an assessment based on what you can see at the time of recording and local knowledge of how the tree may have been managed. Tree form can change over time too.

The most frequently encountered tree forms include:

Maiden

Pollard

Coppice

Multi-stem

But you should also look out for:

Natural pollard

Phoenix

Cliff tree

Coppice (high stump)

Laid (hedgerow) trees

Small stump

Stump (high>4m)

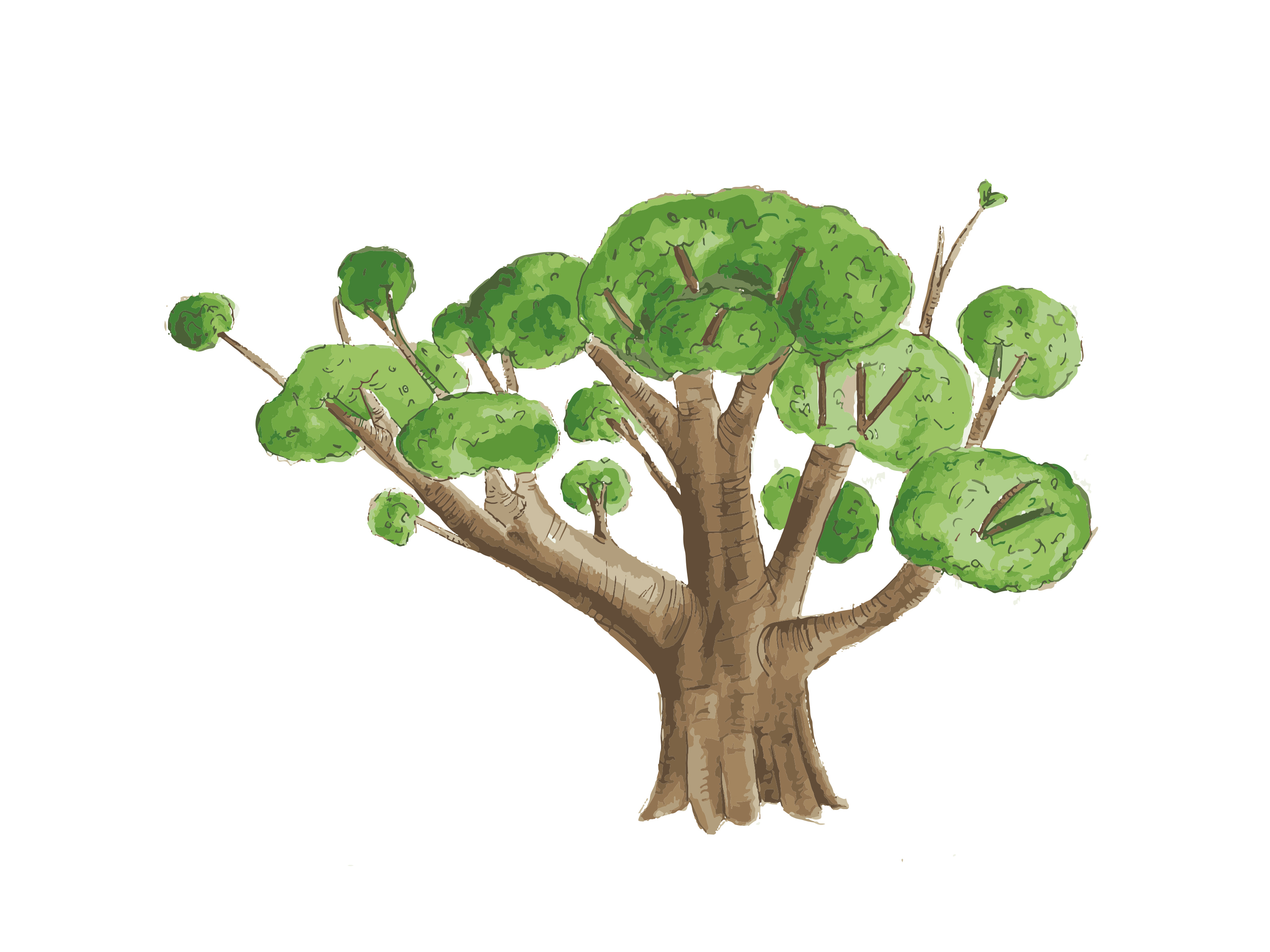

Maiden

The tree has a single trunk to at least 1 m above the ground; it may continue with or without branching or divides into two or sometimes more stems.

There is no evidence of historic management. One or more branches may have been cut, but usually not all at the same height (see Pollard for comparison).

A typical parkland maiden tree. Credit: David Alderman

The 'Majesty' oak; the tallest maiden ancient oak in the UK. Credit: Krzysztof Borkowski

Maiden veteran beech tree. Credit: Richard Wilson

An ancient maiden may be retrenching naturally and may have lost most of its primary crown or its crown may be ‘stag-headed’.

Naturally open grown maiden trees will often have a short trunk forking at a low height with many large branches radiating from this point.

A parkland maiden oak, showing 'stag-headed' appearance that indicates a loss of the primary canopy and formation of a lower 'secondary canopy'. Credit: Jim Mullholland

Open grown tree with a short trunk and wide crown. Credit: David Alderman

Pollard

Pollarding is an ancient form of tree management. A pollard was cut as a ‘working’ tree.

All or most branches, limbs or stems of the tree were (probably) cut at approximately one height above the ground in the past, leading to new growth of branches.

Branches, limbs or stems of the tree were cut at a minimum height of 1.8 m (average 2.5 m), below which it is or was a single stem.

Trees that have been frequently cut have a very distinct hour-glass figure to the stem with a large, often knobbly, ‘knuckle’ or ‘bolling’.

The pollard options that are on the ATI are listed below:

- Pollard (lapsed)

- Pollard (managed)

- Pollard Form (natural)

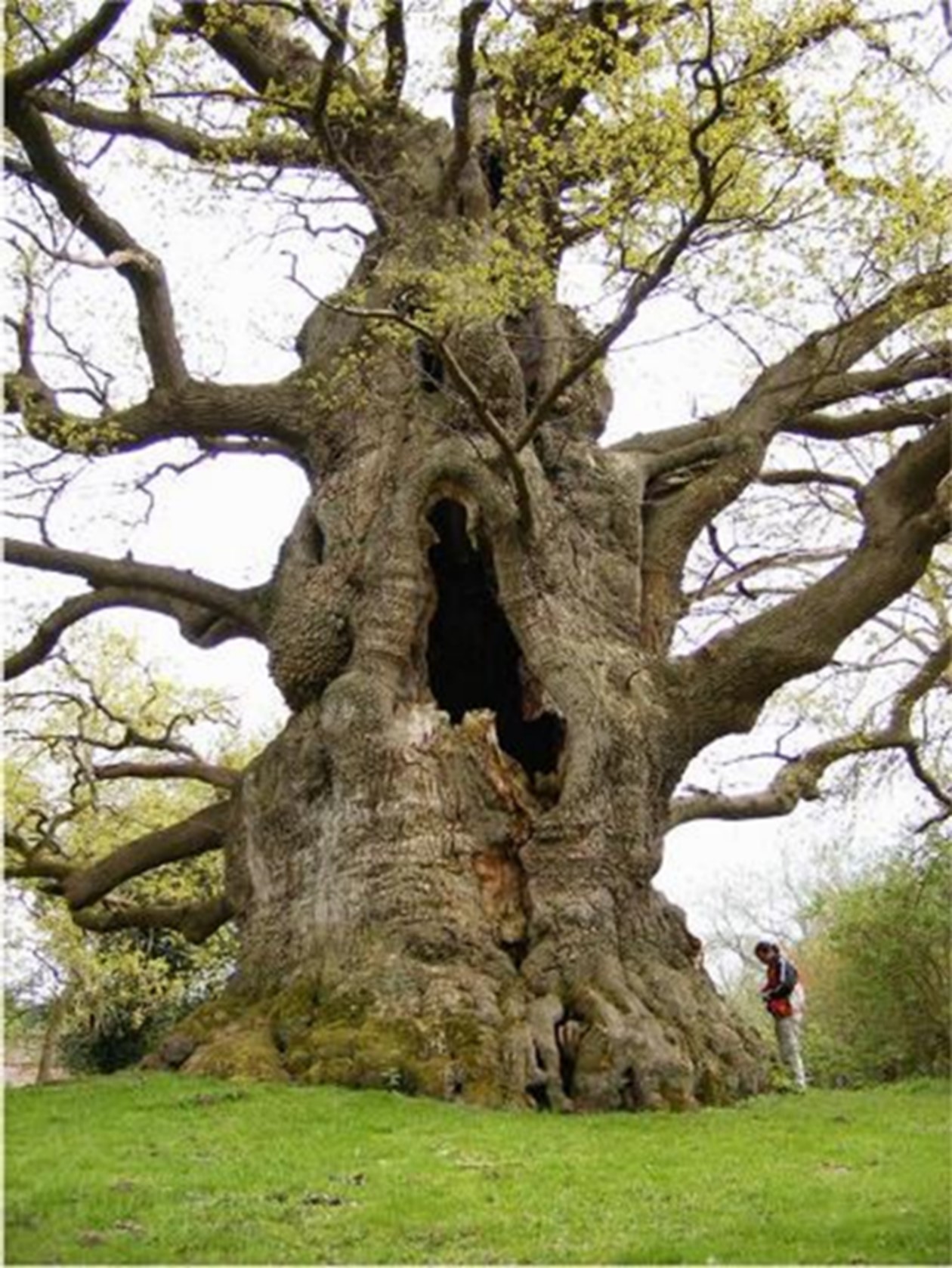

Ancient pollard, cut in the past above 2m height from ground level. Credit: David Alderman

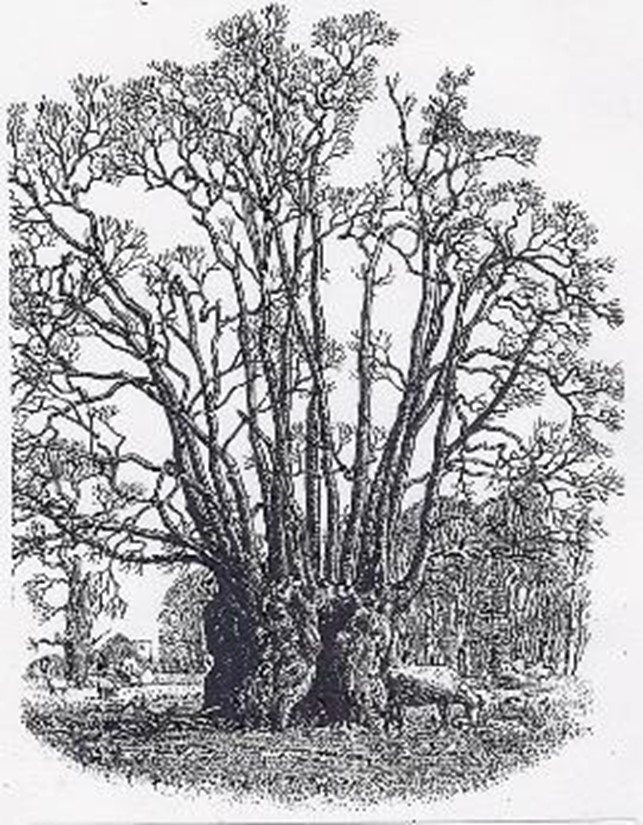

Historic drawing showing a large ancient pollard on a wide trunk.

Ancient hornbeam pollards at Hatfield Forest. Credit: Tom Reed

Pollard (lapsed)

A tree which has been pollarded in the past but has not been re-pollarded will develop a large crown with heavy branches.

Cuts may have happened long ago, the tree may have been cut just once or repeatedly, but evidence of it should be seen. Today many pollards we find will be lapsed pollards e.g. if they are former 'working trees' that were cut frequently in the past, but have not been managed in the same way for a long time.

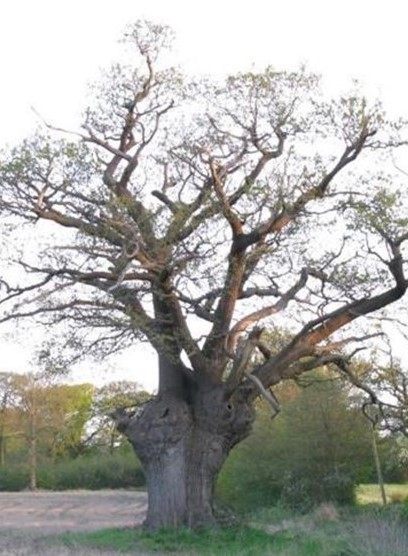

This ancient hornbeam was cut regularly in the past, but has not been managed as a pollard for a long time. Credit: David Alderman

A typical lapsed pollard. Credit: ATI Recorder

A lapsed ash pollard growing on a field boundary. Credit: Gareth Bowen

Pollard managed

A historically managed pollard with evidence that it is still being cut on a regular rotation.

Note: This does not include lapsed pollards that have their crowns reduced at a higher height for safety reasons or maiden trees that have had some infrequent crown reduction.

A row of veteran trees being managed as pollards. Credit: ATI recorder

A veteran willow tree still being managed as a pollard. Credit: Aidan Champion

An ancient ash pollard with old cuts and new cuts clearly visible. Credit: Mark Turner

Pollard form (natural)

Trees that grow in a pollard form either naturally or following injury.

For example, a maiden tree that has lost its primary crown, often from storm damage, or gradual dieback of stem and limbs (retrenchment) resulting in new growth of branches, limbs or stems forming a replacement crown.

Note: Look for other pollards in the area as this may help you to consider whether the tree is an open-grown maiden or a pollard.

An ancient tree that has lost all of its original primary canopy, with a secondary canopy now formed entirely from epicormic growth. Credit: Jim Mullholland

A tree with a naturally-developed pollard form. This tree may not be a true pollard, it is more likely that the original canopy has been lost naturally, with stems growing back to give the tree the form of a pollarded tree. Credit: Rob McBride

Coppice

A historically managed tree usually cut lower than 0.5m above ground, creating a “stool” of many new stems. Ancient coppice will have been re-cut many times and the stump of the original tree may no longer be present.

Over time a coppice stool may become very wide. It may sometimes not be clear if we are looking at one or more coppice stools which have merged. Credit: Leicestershire Orienteering Club

A coppiced tree within ancient woodland. Credit: ATI recorder

What should I do if i am unsure whether the tree is a coppice?

Identifying ancient coppice can sometimes be tricky, depending on what is visible from the remaining coppice stool. If in doubt then record as 'multi stem' and in the comments field explain that the tree may be a potential coppice. Also look for other neighbouring coppice trees, as this will help you to judge whether the wider area was subject to coppicing in the past. See the following examples below.

A large felled tree in parkland, regrowing from around the stump . This is not historic coppice and so should be recorded as a multi stem i.e. because the tree was not deliberately managed as a coppice. Credit: ATI recorder

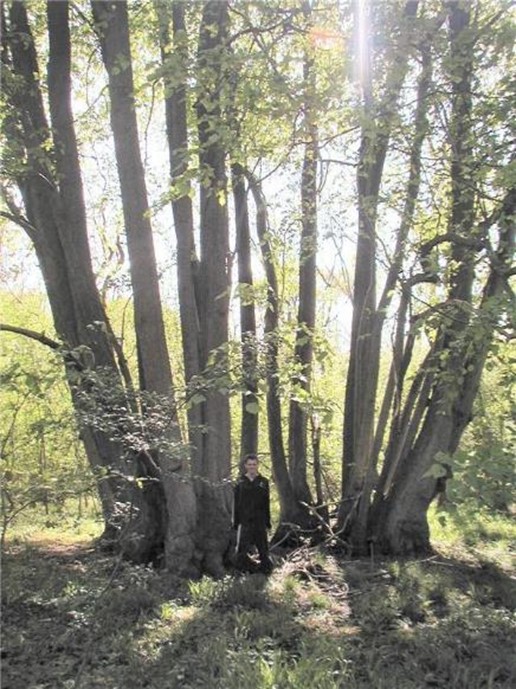

A very large circular group of stems which may, or may not have originated as coppice. If this was a former coppice, then the stool has completely gone, meaning there is very little evidence of coppicing. Credit: Alison Wright

Coppice (high stump)

A variation of a coppice form where branches, limbs or stems were cut between 0.5m and 1.5m above the ground, creating a high stump from which new growth has sprouted.

A typical high stumped coppice stool. Credit: Aljos Farjon

Coppice (high stump). Credit: Aljos Farjon

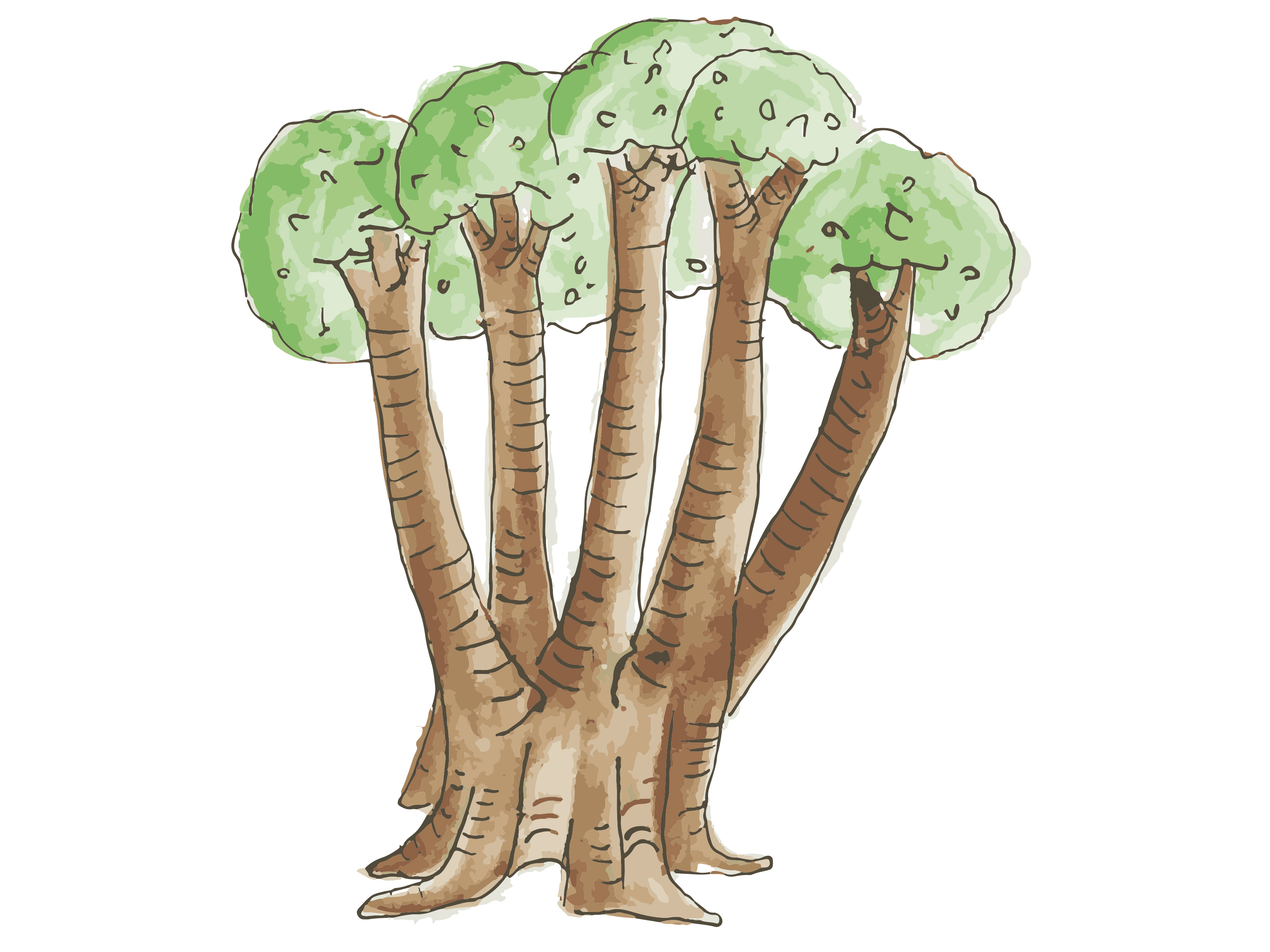

Multi stem

The tree divides into two or more stems less than 1m above the ground, usually from near ground level.

Some species may have stems that are fused to much higher than 1m but the individual stems are clearly defined.

The basal footprint is generally oval if the tree is twin-stemmed and may be more irregular than a maiden or pollard. Many trees will naturally grow with co-dominant stems.

Note: Record as a multi stem tree if the girth measurement is exaggerated by the inclusion of more than one individual stem.

Two trees planted together as part of a 19th century designed landscape. Credit: David Alderman

A fragmented tree may, over time, appear as a multi stem. Credit: Aljos Farjon

Multi stem rowan on a field boundary. Credit: Michael Woolner

Two clearly defined stems which may be two trees growing next to each other or deliberately planted close together. Credit: David Alderman

Multi stem as a 'natural coppice' with several stems joined near ground level (but not resulting from deliberate coppice management). Credit: David Alderman

Multi stem trees can arise from natural or man-made bundle plantings, where multiple stems were planted very close together. Credit: David Alderman

Multi stem (boundary)

This is a tree which is multi stemmed and forming part of a land boundary (whether that be in a woodland or other land boundary) but that has NOT been obviously managed as a ‘laid hedgerow’ (see below).

Trees of this form may be found along woodland rides. It may be planted on top of a man-made earth bank or wall.

Erosion over time may create an exposed root system above ground level.

They will often be difficult to measure the girth with any accuracy due to their irregular and elongated form. The tree may have similarities to being a laid hedgerow but must relate to a historic boundary e.g. a ‘historic wood-bank’.

Tree that has been managed over many years marking a historic boundary. Credit: Alan Hunton

This tree has a complex multi stem form that has arisen partly due to how it has been managed and cut as a boundary tree in the past. Credit: David Carey

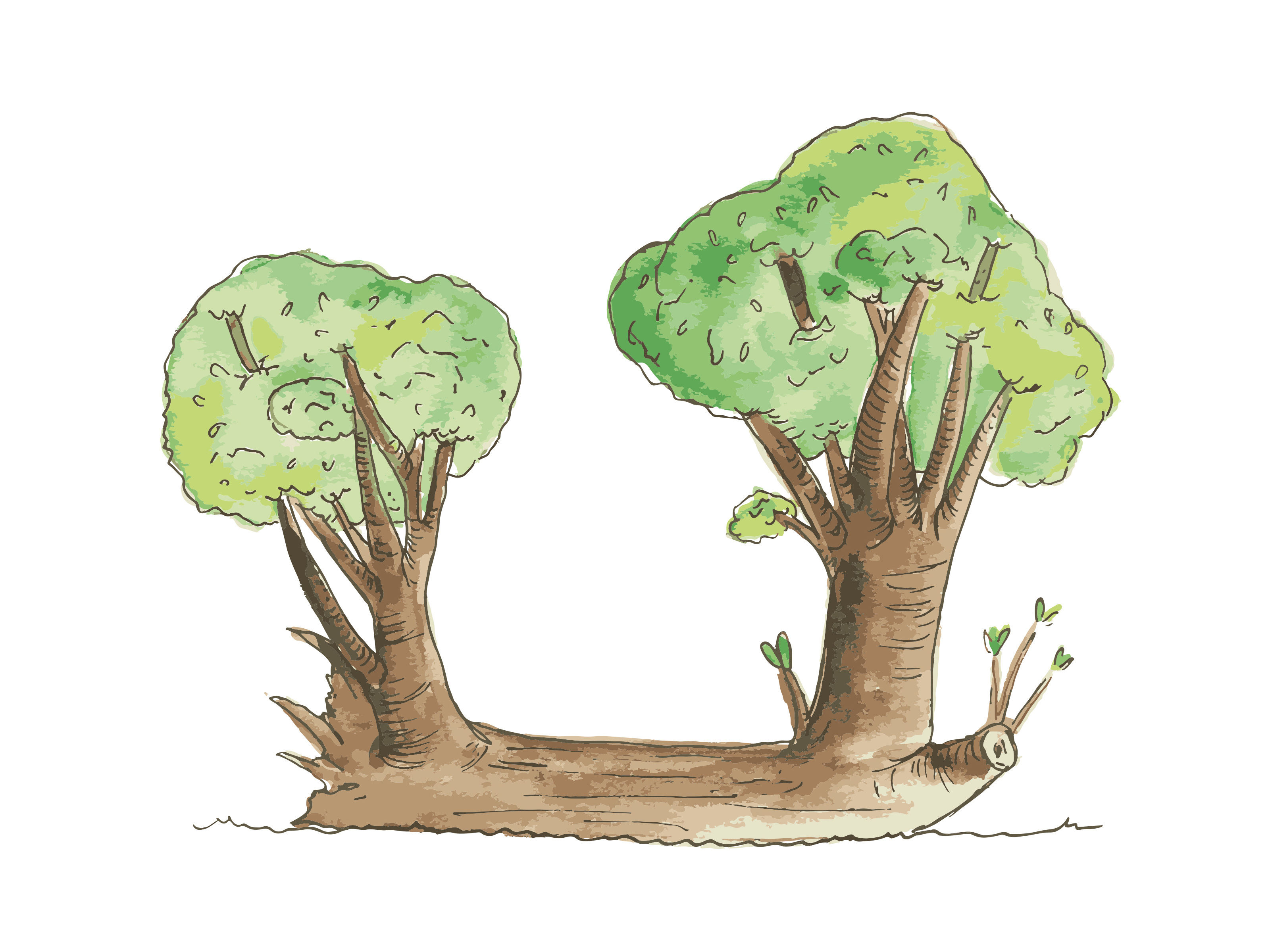

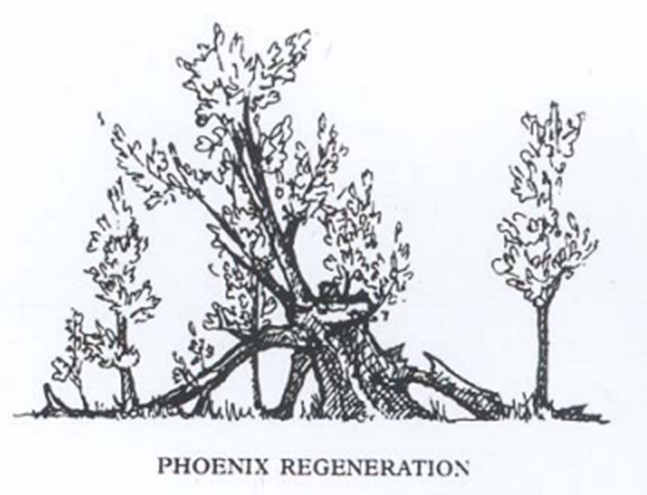

Phoenix

A tree that has originated by natural vegetative reproduction from a fallen or decaying tree, or survived as a fragment of the original stem.

Note: if a tree has fallen but some of its roots are still intact, then the tree may regenerate naturally, although this process can take a long time to develop.

There must be evidence that the tree was part of an older tree which will either be a standing dead tree, a stump, or collapsed and re-growing from the horizontal stem or as a layered branch.

A fallen sweet chestnut that has regenerated from the fallen trunk. Credit: Alan Hunton

Diagram showing an example of phoenix regeneration, with younger stems originating from a much older decaying main stem and broken branches. Credit: Veteran Tree Initiative, Specialist Survey Method

Stump

A stump is less than 4m in height and usually less than 1m.

Occurs as either a cut stump from a felled tree or as the remains of a collapsed or decayed stem.

Stumps are usually dead.

Stump. Credit: David Alderman

Stump (high >4m)

This has a stem taller than 4m in height without any branches.

Usually originally a maiden and usually dead.

It may be the result of a natural break and fractured or deliberately cut high up and retained for its wildlife habitat.

Note: A live tree with a high shattered stump that is regrowing can be categorised as a Maiden or if short as a Pollard form – natural

A high stump. Credit: David Alderman

This is a maiden tree which is still alive and re-growing, despite appearing as a high stump. Look for surviving branches high in the canopy before recording a a high stump. Credit: David Alderman

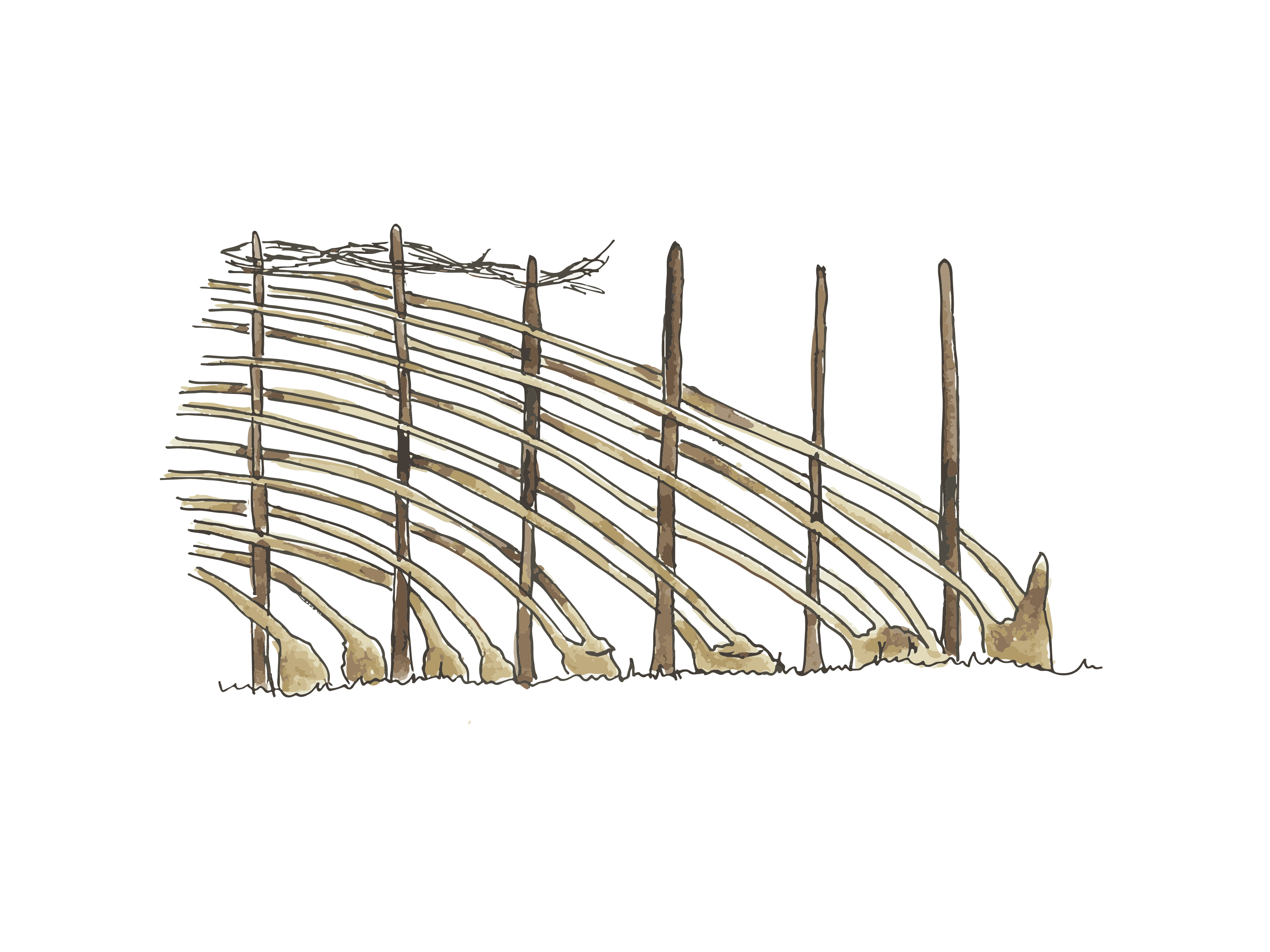

Laid (hedgerow)

A tree that has been part-cut near its base and its stem laid at an angle as part of the historic management of hedge-laying.

May also be later pollarded at a convenient hedge height creating an irregular and complex form.

Usually difficult to measure due to its shape. The girth measured is rarely comparable with another. Take plenty of photos and record the girth close to the base if the tree has many stems.

It is often difficult to identify individual trees – Laid (hedgerow) suggests a “complicated” tree form which may involve more than one tree.

A laid beech hedgerow . Note the leading stem on the right at a 45 degree angle which indicates that this tree was part of a historic laid hedgerow. Credit Jamie Simpson

Laid hedgerow tree. The angle of the stems shows how the younger branches were guided in the past as part of laying the hedgerow. Credit: Karen McLellan

Cliff tree

These are trees that are generally growing out from the face of a vertical cliff.

Often they do not have a clearly defined single stem.

And the girth measurement is frequently estimated for safety reasons!

A cliff tree. Credit: David Alderman

A tree growing from a steep eroded bank. Credit: Vanessa Champion

Trees growing on top of unstable ground may end up as cliff trees due to erosion. Credit: Vanessa Champion

Unknown

If you are unsure which option to select, please record as 'unknown'.

Tree form may change over time. And it may be that a tree has grown, been managed or been damaged in such a way, and over a long period of time, that its tree form can not be allocated with confidence to any of the above types.

It is therefore reasonable to allocate “Unknown” in these circumstances.